This is a somewhat brief post, as finishing up narrative reports for independent school applications and administering the ISEE test at Miquon on Saturday have taken up a lot of time.

As our study of the westward expansion of the United States winds down (more on that in our next post), we are getting ready to begin our very ambitious study of Ireland from earliest times to the present. It’s a continuation of our year-long theme of migration, and it will include many different kinds of and reasons for arrivals to and departures from this island of “saints and scholars.”

As a bit of a preliminary teaser, we have been working recently on a short mummers play. Customarily done during the winter season and most especially on December 26th, this is an ancient tradition whose origins are fuzzy and the subject of much debate. You can find more information about mumming and mummers’ plays here, here, and here — along with many other online and print resources. Are the famous Philadelphia Mummers part of this heritage? They may well be.

December 26th — in many places, including Ireland, England, and Scotland — is known as Wren Day and also as St. Stephen’s Day (along with “Boxing Day” — a time to give gifts (in boxes) to employees and more distant friends). The hunting of the wren at this time of year is older than Christianity but has acquired a connection to Christian belief. There are indications that it has its tangled roots in winter rituals from the Celts and/or the Vikings — celebrations relating to death and resurrection, which is a common theme connected with the winter solstice and the turning of the year from darkness to light. There are countless variations of the song we are doing that starts with: The wren, the wren, the king of all birds, St. Stephen’s day was caught in the furze . . .”

How did the little wren become the “king of all birds”? One traditional story that we shared with the class is that the birds decided to elect a king by holding a competition. The bird that could fly the highest would win. As the birds took to the sky and dropped out one by one, only the eagle was left, soaring high above the others. But just as he was about to be declared the winner, a little wren that had been hiding on the eagle’s back flew out and rose above the exhausted eagle. The wren flew the highest and was declared king, but all of the other birds recognized the trick for what it was, and the wren was regarded as treacherous and not to be trusted. We now move to Christian times and the story of St. Stephen. Stephen was a Christian who was persecuted and hunted for his beliefs. As Roman soldiers were searching for him, so the story goes, he took refuge in thick shrubbery. But a wren flew out of the bushes, which gave away his hiding place. He was captured and stoned to death. So, once again, the wren was seen as untrustworthy.

There arose in Ireland the tradition of hunting and killing wrens on Dec. 26th and taking them around to houses as a form of entertainment and begging for food, drink, and coins. The money was ostensibly to purchase a coffin for the wren but almost certainly went to the local publican instead. Plays were developed as part of the practice, almost always featuring a battle between two enemies and then the death and resurrection of one. Early winter solstice plays were said to be silent (“mum”) but gradually evolved into a rhymed structure.

In any case, we have talked a bit about these complicated beliefs and practices in class and put together a mummers play of our own, based largely on ones done in the Northern Irish county of Armagh. One of the common features of these plays is a sword dance. We are doing an abbreviated one, with thanks to John Krumm for bringing it to Miquon many years ago when he was our music and dance teacher. Mark and I were struggling with the intricacies of the dance and, in particular, the way to end the dance by weaving the swords into a star.

Finally, from our desperate searching, we found this very interesting website, where the mathematical aspects of the sword dance are explored in detail. The third iteration of the dance pattern gave us what we needed. Our play has several large parts but also several very small ones in order to give every student at least one line to say alone. By doing the sword dance with eight students, everyone was able to have a share in the production that was important. We assured students that we would be doing a much more elaborate and lengthy play later in the year — that this was just a little bit of theater — but a few were initially disappointed in how our random casting method had worked out for them and were happy to be the participants in the dance.

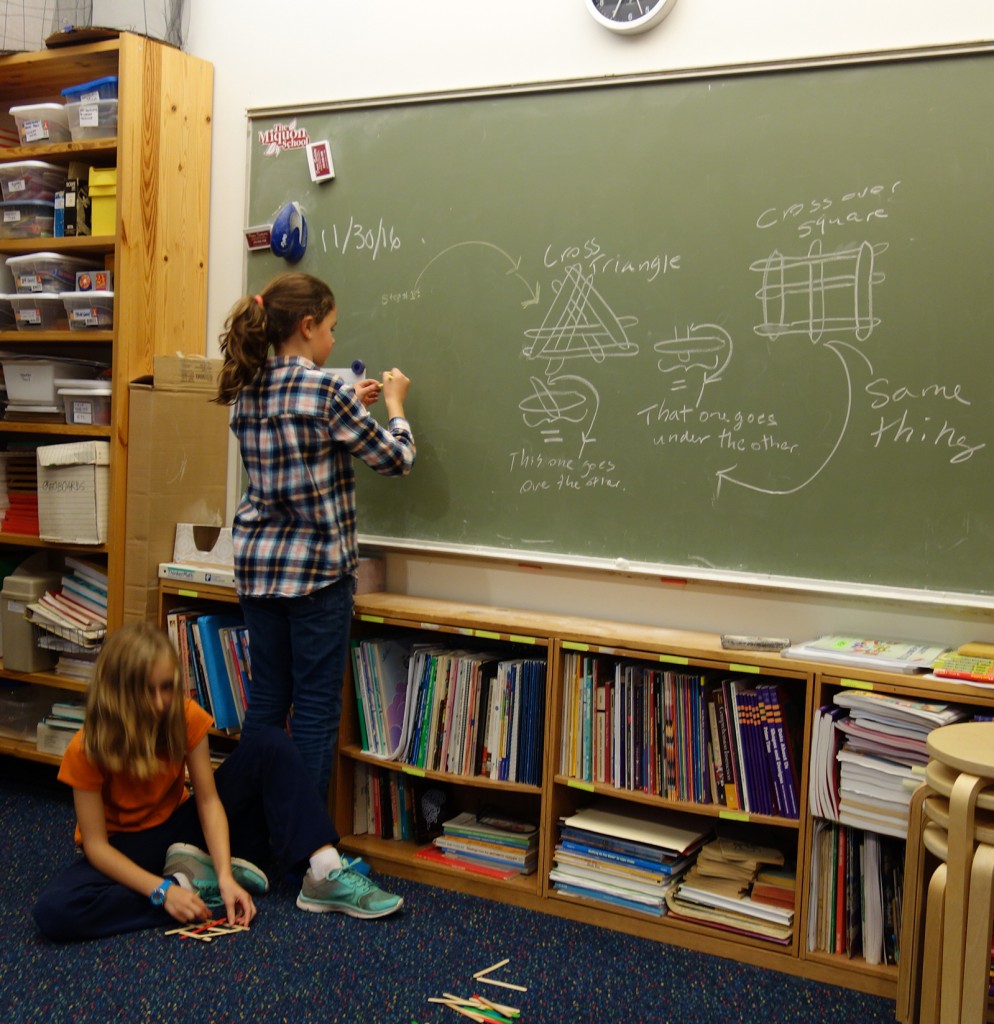

The site that went into the mathematics of sword dance patterns also introduced us to something totally new: “popsicle stick bombs.” The mathematical concepts that underlie the weaving patterns of the swords can be translated into structures made from craft sticks. Four or more sticks are woven into tight structures, and they “explode” in a very satisfying way when they are thrown onto the ground. We had a wonderful time working out a successful ending to the sword dance and then creating those craft stick bombs during two afternoons. There was a lot of good problem-solving, observation, analysis, and collaborative building as students tried to create structures that incorporated four to eight sticks into a rigid (but volatile) pattern. One of our half groups worked very hard on doing as many of the website modeled structures as possible. We spent time on thinking about the weaving patterns, led by a spontaneous and very inspired summary on the chalkboard by one of that half. The other group divided into two camps and decided to build a supply of “bombs” in order to have a war with each other. With them, we talked about the fact that having a weapon frequently leads to a desire to use it — a serious moment in an otherwise very playful class.

We had some visitors on the second day who were coming to see play and Progressive education in practice — they were delighted and amazed by what we were doing with sword dancing and craft sticks.

We are planning to perform our short mummers’ play for the school on Thursday, December 15, when we are doing a dress rehearsal for the winter assembly. Time permitting, we may do it as part of the community assembly on the following day as well. Stay tuned.

Maybe this was not such a brief post after all — there is always so much to share at the end of a week, and this is still just a fragment of what went on. Next week, we’ll tell you about the end of the wagon train simulation and our related exploration of the Exodusters, thanks to Mark’s research and planning of this important part of post-Reconstruction history.