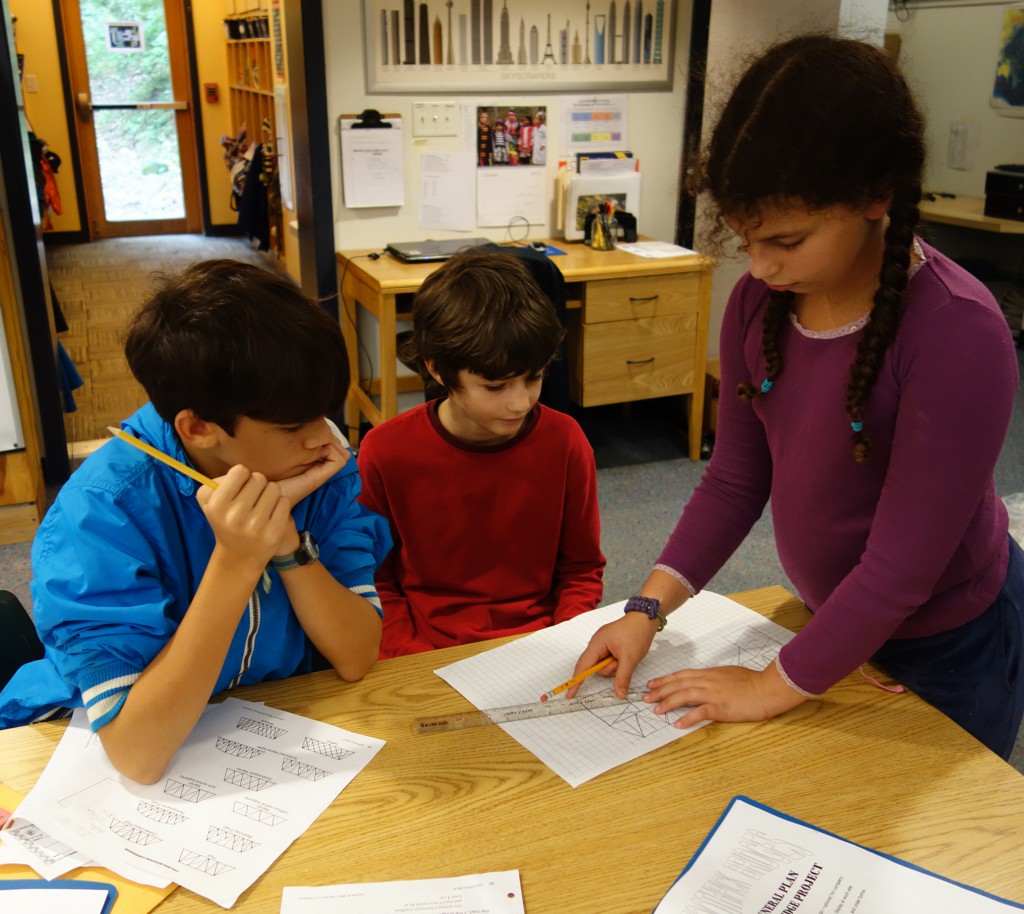

Bridge research is well-launched at this point. Students are working on it at school and — as time permits — at home. The approach we are taking is different than the self-selected animal presentations students did in September. We are asking students to share their research through a talk that is supported by images. That is, we want very little text on the slides, which should be pictures of the bridge, maps to show us where it is or was located, and images that are not bridges but relate to the subject. Possibilities include original design plans. a “tour” of the bridge via Google Earth or a video, an image and information about the person after whom the bridge was named, images of newspaper stories about the bridge, and whatever else seems to enhance the researcher’s talk.

The last stage of our work will be to invite students to make some decisions about having slides that do contain some text. What would be better understood by your audience if they could see it as well as hear it from you, and why? A likely suggestion would be some of the statistics that involve large numbers: the cost to build the bridge, for example. Large numbers are hard to take in if they are just stated. But we’ll see what the students decide.

We will be working next week on beginning each child’s collection of 3 x 5 cards to assist them with their presentation talk. They are still gathering information, but we can teach the process without needing their facts to be complete.

The challenge of note-taking for many students at this age is achieving brevity. It’s somewhat ironic — we’ve spent several years developing their ability to write in complete sentences. Now we are asking for notes, most of which will NOT be complete sentences. This summarizing and selecting requires some analytical thought. What are the essential words in the facts I want to record? The source said The Royal Gorge Bridge is the tallest bridge in the United States. A useful note taken from that sentence would be tallest in USA. We don’t need the name of the bridge because it’s the subject of our report. We don’t need the word bridge. We can shorten United States to USA. We want to keep the location in our note because this is not the tallest bridge in the world, just in the United States.

That’s a lot of decision-making, and some students at this point in school find it difficult. We are asking them to do this on the subtopic document where they are recording their information as well as on the 3 x 5 cards that will act as prompts for their talk. Next week, we’ll be going through their subtopic documents with them to identify places where they could use fewer words and where they have made the kind of notes we’re expecting.

One of the benefits of taking notes like the example above is that it is likely to reduce accidental plagiarism. Another benefit is that students are more likely to ask about things they don’t understand because (we hope) they will see the need for full understanding in order to distill the sentences into essential words.

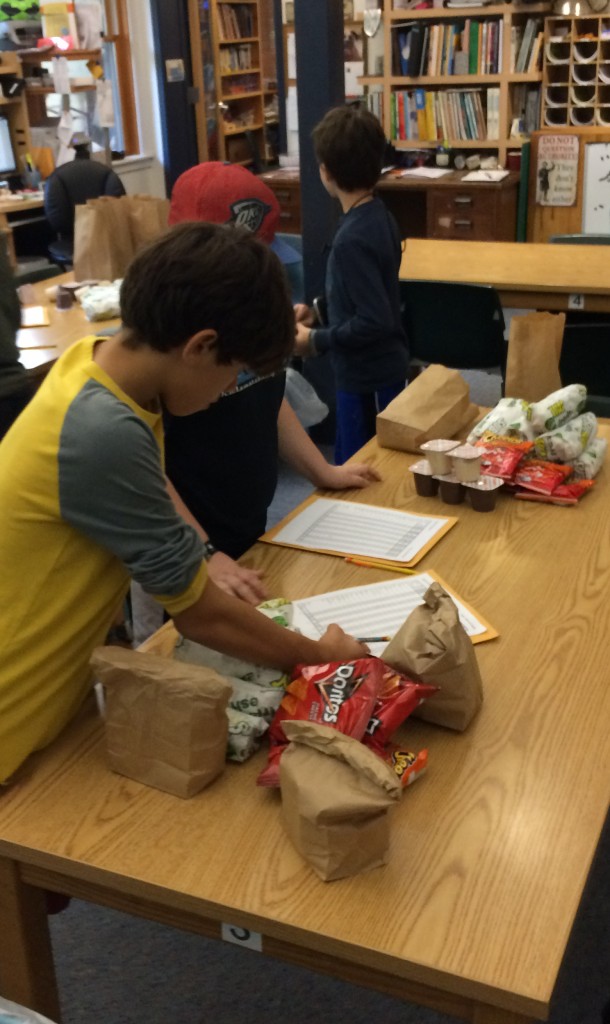

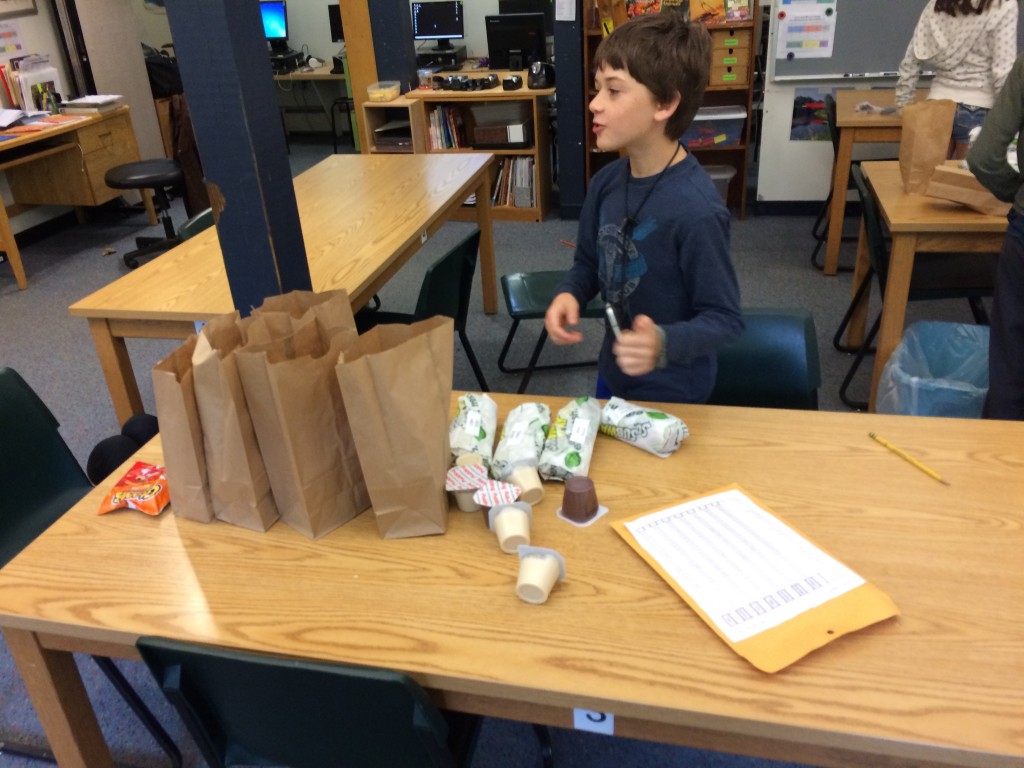

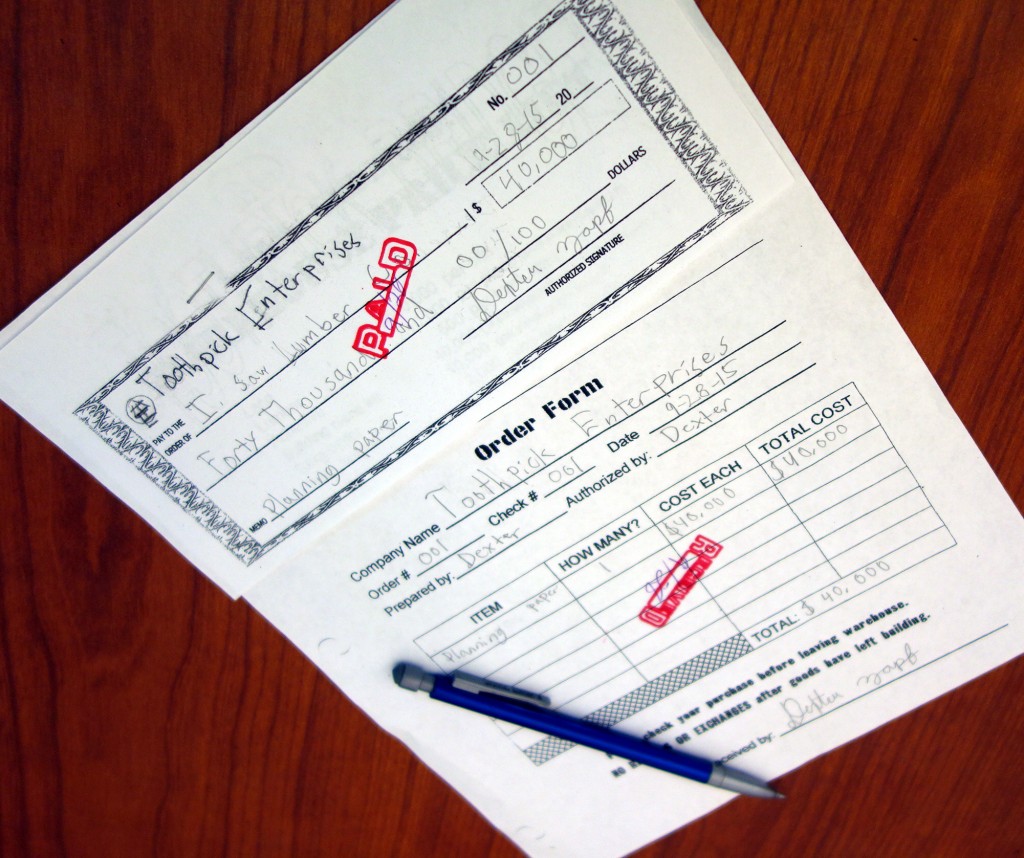

Bridge Bookkeeping took on a new aspect Thursday. Mark and I had each team gather its canceled checks and order forms, make sure their bank account balance sheet was correct and up-to-date, and bring it all to one of us for an audit. Several teams had their accounts in good shape: everything was recorded, and the numbers were accurate. Several teams, however, did not do so well. Some had more or less money than they thought they had, mostly because of errors in subtraction on their balance sheet. One team had recorded a check incorrectly and “fixed” it later by adjusting the amount of a different check when they put it on their balance sheet. Their final balance was correct, but we sent them back to clean up the original error so that every check matched what was recorded.

We had a good life-skill discussion about this. We talked about the importance of knowing how much money you have in the bank and what happens if you accidentally spend more than that. I said that many of their parents did their accounts online or with software and transacted most of their business with credit or debit cards. I added that they were likely to do the same when they were keeping track of their income and expenses when they are older. But paper checks still have a use, as they saw when someone paid us for their child’s Friday lunch this week. The check looked a lot like the ones students have been writing for their bridge supplies, much to their delight! We hope parents will find some time to show their children how they keep financial records at home or for a business. It would connect our classroom financial lessons to real-world economics.

Mathematics instruction in several of our 8 small groups has included written and mental computation skills for addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. It is not unusual for fifth and even sixth grade students to have difficulty with subtraction and division. I can think of several reasons for this which arise from research as well as from my own years of observation. In my opinion, much of the confusion comes from spending too little time securing the concepts with concrete experiences and lots of application opportunities before moving on to an abstract written process. Another issue is connected with language.

One pervasive cause of mathematics difficulty in the early years is the English language, where we can hear and see inconsistencies as soon as we move into numbers in the teens. We say sixteen but we write 16 (ten-six). Worse yet, eleven and twelve give no hint of their two-digit nature. If you know any other languages, consider the number nomenclature. Is it like English, or are the words for numbers from 11 through 19 built from parts in the same order in which they’re written? English tends to be the exception.

The language problem becomes worse when we think of the many fuzzy words and phrases we typically use for division:

Sixteen divided BY eight equals two.

Sixteen divided INTO thirty-two equals two.

Sixteen divided INTO eight groups equals two (in each group).

Sixteen INTO eight equals one half (of a group).

Sixteen GOES INTO thirty-two two times. (Two times what? Are we multiplying? In fact, we are: two times sixteen is thirty-two.)

For many students who are wobbly about writing division as an equation, some structured language can help. For example, 16 ÷ 8 = 2 may make more sense if a student “reads” it as I have sixteen. I want to break sixteen into groups of 8. I can make two groups. That’s a lot more language than Sixteen divided by 8 equals 2, and it contains much more mathematical meaning. However, even this is incomplete. Does that equation mean that we want to know how much will be in each of 8 equal groups or how many groups of 8 can be created? We could say I have sixteen. I want to make 8 groups. I can put two in each group. Does it matter? Some sort of narrative context could help.

We were doing some work with multiplication and division fact families with some fifth graders. Given the numbers 48, 6 and 8, they were instructed to write two multiplication and two division equations. Some did what was expected:

6 x 8 = 48

7 x 6 = 48

48 ÷ 6 = 8

48 ÷ 8 = 6

But several ran into trouble with division. They wrote the division equations like this:

6 ÷ 48 = 8

8 ÷ 48 = 6

I’ve wondered if this error may be connected to the way division is typically recorded for calculation:

![]() In some cases, students wrote one division statement correctly but not both. Some thought the order didn’t matter. Discussion with everyone revealed that even some students who did all of the equations correctly had limited understanding of why they were written as they were.

In some cases, students wrote one division statement correctly but not both. Some thought the order didn’t matter. Discussion with everyone revealed that even some students who did all of the equations correctly had limited understanding of why they were written as they were.

Teacher: Why did you write the 48 first?

Student: Because it’s the biggest number, and you always write the biggest number first for division. [This student is in for some new ideas when we take up fractions.]

Teacher: Why do you think that’s true?

Student: That’s just how you do it. [Oh, dear.]

This whole topic could easily become a 100-page essay here, but I’ll point out just a few more things. One is that, if we teach multiplication and division (or addition and subtraction) by focusing only or primarily on them as opposites, students may lose track of the fact that addition and multiplication are two forms of the same thing. One attribute those operations share is that you can do the computation in any order. Subtraction and division are also two forms of the same thing. One attribute they share is that order matters.

Another thing that may confuse students is the misleading similarity between the way we often write addition and subtraction to do a calculation by hand:

They look very much alike except for the operation sign. But addition involves two separate quantities that can be combined in any order. Subtraction involves ONE quantity and the amount that is to be removed from it. And you can’t do it in any order.

I think this is why many students, even in fifth and sixth grade, faced with doing the subtraction in the tens place (6 tens minus 7 tens) will simply record the difference between the two numbers (1) instead of regrouping from the hundreds place and creating sixteen tens from which they can remove seven. We need to ask students what they are thinking as well as observe what they are writing. If they are focusing on the difference between two separate quantities (562 and 272) but doing it one place at a time, they are likely to decide that the overall difference is 310 instead of 290.

Conversations about concepts often show that students who do subtraction correctly simply have a very sturdy memory of how to do the process but not an understanding of why it is done that way. When we ask students to solve the subtraction problem above using objects on a place-value chart, some will arrange their Cuisenaire rods, Dienes blocks, or other manipulatives to represent both numbers, one above the other, just as it was written here. They don’t recognize that the number being subtracted is already there when they have placed 562 in the chart, including some who can do the paper-and-pencil algorithm correctly.

What are we doing about all of these computational and conceptual wobbles? We’re doing several things. One is working on language, trying to clarify terms and develop more explicit ways of creating and interpreting an equation with words, as described above. Another is that we often use manipulative materials (such as a pile of plastic squares) along with as well as before doing written processes. A third is that we do a lot of practice with these operations in a narrative context. If the situation involves sharing 8 cookies among 16 students, students are likely to recognize that it is cookies which are being divided, although they may still write the equation incorrectly. (“You always put the biggest number first.”) . A fourth tool is that of rounding and estimating the answer before or after doing the computation — is your answer reasonable? Finally, we often ask students to check their work by doing the opposite operation: add to check subtraction, multiply to check addition. Essentially, undo what you did and see if you end up where you began. These are things that will be part of all of our work in mathematics, whatever the topic.