Our two performances of our play, “On Camera, Noah Webster” went off with any major problems. Everyone put it all out there to make it silly, serious, and — above all, as Dexter said — educational. Students learned challenging amounts of lines with a lot of new vocabulary and expressions, made rapid costume changes, interacted well with each other, and felt very pleased with the way the audiences (students and parents) responded. Thanks go to the parents who provided snacks and helped with cleaning up the Moore building at the end.

The alligator project has just about come to an end. We have finished all of the measurements and sent our ‘gators home. They will “grow” again if students put them back in water.

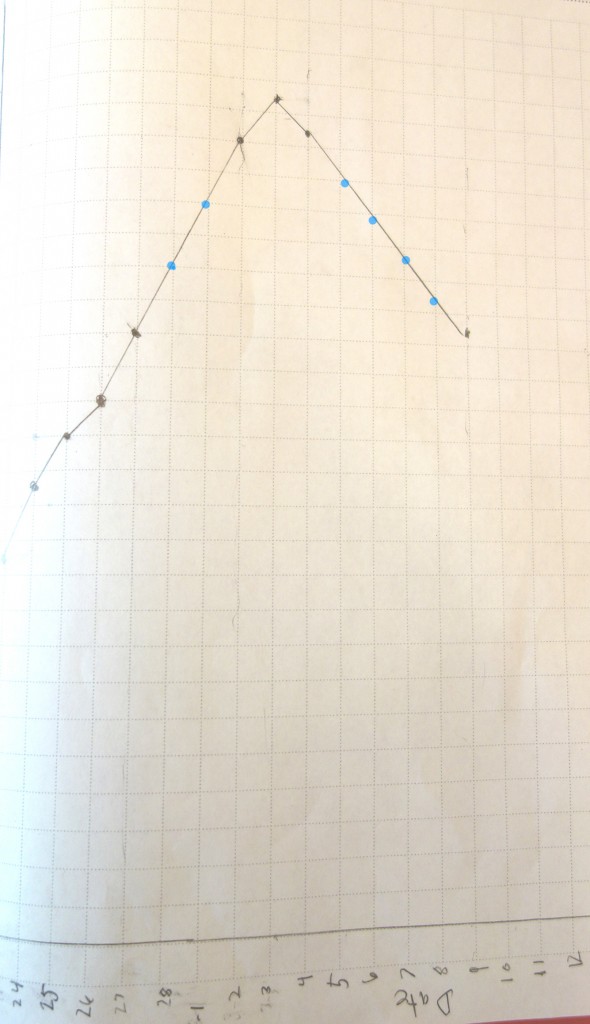

The final math activities involved making line graphs from our data: length, girth, and mass. Then we looked at the places on our graphs where we had not measured the critters because of weekends and snow days. We could see that the line passed through those blank spots and that the lines were fairly straight, which meant we could make a reasonable estimate of what the measurements would have been. We used colored pencils to differentiate between the data points that were from measurement and the ones we put on the non-measured days. Students added interpolate to their math vocabulary.

The only thing remaining for this project is the final editing and sharing of the stories students wrote about their alligators. We discussed what makes a good story — characters we can understand and some kind of central problem or goal that the main character(s) have to address. We mentioned that some of the signposts from our Notice and Note lists might help with the story, too. When we get back from Spring Break, we’ll share, revise and edit, and discuss these very varied “gator tales.” I must confess that I thought students would spend a day or two on creating a short fable, but our novelists have taken it to the next level (again!)

As part of our quick unit on the Celts and Romans, we started learning to play what is believed to be an ancient game from Ireland: brandubh (BRAN- doov, which means “black raven”). I really like games in which the opponents have different numbers and/or types of pieces and separate winning strategies . . . and this is one of those. What several of our students learned on the first day of playing it is that you have to play a new game a number of times before you can play strategically. We’ll get back to this game after the break.

We sent our “Roman” oil lamps home on the night of the play. Several students have worked on testing theirs already. They should all be tested and the experimental comment sheet completed and brought back to school on April 1. Here’s a photo that Jonah’s dad took of Jonah’s greatest success:

As we learn about the cultures of the Celts and Romans and what happened as the Romans brought their armies and engineering genius to more and more of the world, one of the things we are talking about is the parallel we can find between that piece of history and what became of the indigenous peoples in North and South America when Europeans arrived.

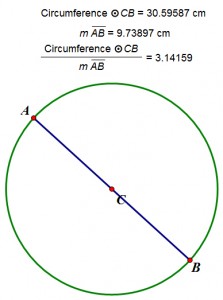

The date of Pi Day this year was special: we not only had the month and day matching the first 3 digits of pi (3.14) but also had two more digits in the year: 3.1415. I suspect that many of our students will always remember pi to at least 4 decimal places because of that. But what is pi? We used our math time to find out. Students were given tape measures and turned loose in the classroom to measure and record the circumference and diameter of as many things as they could. They were surprised to discover just how many round things we had. (A few wanted to measure people’s heads, but we were able to convince them that heads are not actually round.)

Then we got out our calculators and divided each circumference by its diameter. Just about everyone found that the quotients were somewhere around 3. We agreed that our measurements were not as precise as they would need to be in order to get a true value for pi, but the approximate values were pretty good. We then went to our computers, got Geometer’s Sketchpad going, and used the tools to create a circle and draw its diameter. After getting the built-in calculator to do the math, students changed the size of the circle and could see that C/D was equal to 3.14159 constantly, even though the numbers for circumference and diameter changed. Why did it stop at 5 decimal places? Just because that’s all the software was capable of providing.

So pi emerged as a relationship. Why does it have a name? Because it’s an irrational number — it cannot be precisely written as a decimal number or as a fraction. So any numerical naming would have to be approximate. (Compare this to 1/3. We can’t write it accurately as a decimal number because 0.33333 . . . goes on forever. But we can write it accurately as a fraction.) The best we can do with pi is give it a name.

We took the exploration a bit further by seeing if there was anything similar about measurements we could do with a square. So we drew squares of various sizes on Sketchpad’s grid. What else should we draw that would be comparable to the diameter of a circle? A few students suggested that one side would be right. But isn’t that part of the perimeter of the square? And is it the longest segment we can draw? Aha! A diagonal is what we need. So we measured the perimeter of a square, divided it by the length of its diagonal, and again found a constant relationship. No matter how we changed the size of the square, when we divided the perimeter by the length of the diagonal, we got the same result! It was an interesting extension of our traditional “discovering pi” activities.

We finally completed the students’ Life Skills 101 presentations just in time for our break. Network problems, weather, and students’ (un)readiness pushed us to the edge, but it all worked out.

The choices they made were delightfully varied: food preparation, doing laundry, cleaning up and organizing a space, redecorating a room, grocery shopping . . . all of them being things that are important to know about and that helped with some of the work that keeps a home and family comfortable.

Their presentations included descriptions of some unexpected problems — forgetting a key ingredient in a recipe, spilling the laundry detergent, setting fire to a kitchen towel that was left on the stove, putting things in the food processor without installing the blade, and more. We could all laugh about it because it worked out in the end.

Students came away with a deepened appreciation of the amount of time their parents spend on such jobs, and several are planning to keep their new skills sharp by continuing to do the tasks they have now mastered. They all are very proud of what they accomplished, and so are we.