Check back for our final blog post, where we’ll have pictures and descriptions of our camping trip and personal projects. Thanks to all of the parents who helped with our trip — not only for your work but also for arranging perfect weather.

Weeks of May 17 and 24: Wrapping Up Many Things

Our literature-based study of the internment of ethnic Japanese during WWII came to an end with a wonderful whole group discussion. We started by asking about the many different kinds of migrations that were part of the entire history. Students came up with quite a few: coming to America from Japan in the first place, sending young people back to Japan for their cultural education, being moved first to holding centers and then to camps, being transferred from one camp to another, being released from the camps to attend college in the Midwest and East and to enlist in the army to fight in Europe, and leaving the camps to go back home or to a new location when they were closed.

We talked about the lack of facilities and proper supplies in the camps that was changed very little during the entire internment period — housing, privacy, bathrooms, food, medical care, schools and equipment, recreation, and more. Students were keenly aware that circumstances in the camps destroyed family life, in part because many adults were ashamed by their incarceration, depressed by the lack of things to do that would make them feel productive, and unable to control their children and adolescents. The large dining halls meant that families did not have to eat together, and this led to a loss of control over the children and teens. On the other hand, our students pointed out that some things did turn out to be good — some residents were able to learn English for the first time; some started schools for children and cultural activities for the adults and were pleased with new-found leadership skills. We talked about the irony of being encouraged to join the army after being locked up as potential traitors with no evidence to support that concern. Several already knew about the courage and heroism in the all-Japanese fighting units.

Students were quite eloquent about what they thought the American government should have done from the beginning of immigration from Japan: allow ownership of land by non-citizens, permit them to become citizens, and “Welcome them and protect them when the war broke out,” as one student said. They saw that some Japanese people became politicized against the USA because of how they were treated after Pearl Harbor, despite being loyal until that time. Our students were also able to see the connection between the fear and racism of that period with the hostility toward Muslims now. There is a very keen sense of social justice alive and well in our classroom.

We’re also coming to the end of our study of Ireland. We went to see the Irish Famine Memorial on the waterfront in Philadelphia. The massive bronze sculpture showed a complex blend of crop failure, despair, emigration, and arrival. Students were able to identify all of those elements. They realized that it must have been created in a manner similar to that used for the Famine Ship sculpture located at the foot of Croagh Patrick in County Mayo, which we learned about in a documentary some weeks before. They read the 8 informational plaques that are part of the part that surrounds the sculpture and agreed that a person who knew nothing about the famine and the socio-political events surrounding it would come away with a lot after visiting the site.

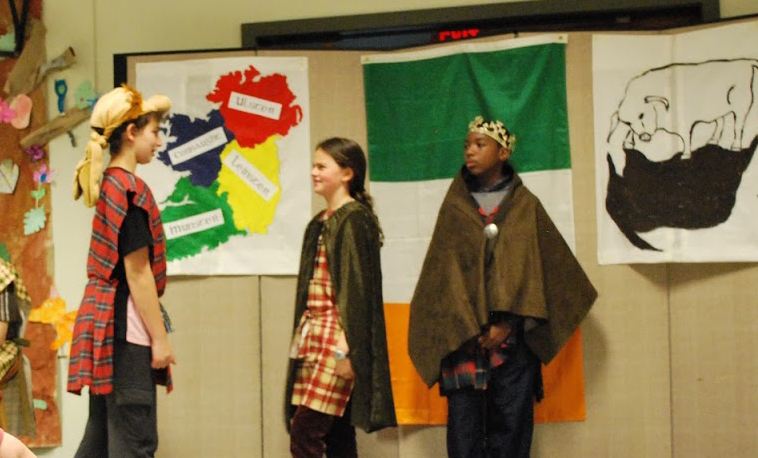

We’re well into 20th century Ireland now. We’ve addressed “The Troubles” with a fairly gentle hand, thinking that some of it is probably more appropriate for our students when they are a bit older. The acts of terrorism conducted by both sides as well as the hunger strike that led to the deaths of 10 prisoners in the prison known as The Maze (Long Kesh) in Northern Ireland involve a level of political and emotional complexity that would be difficult for many of our students to understand right now. On a lighter note, their performances of The Táin and their pennywhistle playing were a delight to see and hear.

We are now in the midst of watching the film Into the West, which is a wonderful story in itself and also provides some insight into the lifestyles and conflicts of Irish travelers in recent years — some of whom have responded positively to government encouragement to become “settled” and ultimately assimilated. Others have had a lot of success in the courts for being recognized as a distinct ethnic minority who are entitled to maintain their nomadic culture and traditions within the larger Irish society.

We have just a couple of Wednesday sings left in the year. Last week, we invited the students who will be fifth graders in our building next year to join us for one. Our current fifth graders also hosted them for lunch in our classroom while I met with the current sixths in Diane and Jeri’s room to continue working on choosing their gift to the school. We are keenly aware that it’s a time of transition for all of us. Graduates are working on their speeches, and fifths are putting together the skits. The end is near.

Week of May 8: The Educational Side of the Spring Fair

Although we don’t often have rain on the day of our spring fair, it does happen. As a result, we always choose a game that can be played indoors. Designing the game and its rules is always a learning experience as well as a lot of fun. In the last few years, we linked that game (whatever it was) to the “Flush Bucket” activity — one in which a volunteer adult or student sits under a water-filled bucket attached to the basketball back outside of the library. When someone wins the game, students ring the dreaded gong and pull the rope that dumps the bucket. Sadly, this was one of those rare rainy years, so we had an indoor fair. The Flush Bucket stayed in storage. The fair was great fun, nonetheless, and one of the incidental benefits was that parents had a chance to see all of the classrooms as they toured the games and other activities.

Our first game involved making a pachinko board, which is kind of like a primitive pinball game. I had built a little one for the class during the “Workbench” minicourse a few weeks ago, hoping (in vain) that kids in the minicourse would be inspired to make one of their own.

Our first game involved making a pachinko board, which is kind of like a primitive pinball game. I had built a little one for the class during the “Workbench” minicourse a few weeks ago, hoping (in vain) that kids in the minicourse would be inspired to make one of their own.

Kids have played this one constantly in the classroom, however, so building a big one for the fair was a choice that the group endorsed. A 2 by 4 foot piece of MDF seemed like a good starting place, and we thank Mike Batchelor for getting it for us.

After we framed the MDF with some 1 by 5 pine, it was time to work on the interior obstacles. During several choice times, kids used soft-tack putty to position assorted items and see how the marbles rolled. As always, they thought of clever ways to use things from our maker area that would never have occurred to me.

There were five compartments at the bottom of the board. Were they equally likely to end up with a marble? We did a lot of data-gathering. By now, most of our kids know that a data sample has to be large in order to give a valid indication of the pool it represents. How many times (“What percent?”) did a marble end up in each of 5 compartments? The first few rounds seemed to favor one compartment. After a lot of rounds were played, we could see that four of the compartments were fairly equal in likelihood, while the fifth was much more difficult to hit. We discussed changing the pieces but finally decided to make that elusive compartment worth more points. Students secured the pieces with hot glue, and we were ready to move on.

Creating the rules for play is always an interesting process. Students invariably start out with ideas that are so complicated that the fair would be over by the time they finished explaining how the game worked. We reminded them that we wanted the game to take some time — that kids will run through their supply of game tickets too quickly if the game’s playing time is too short. We finally settled on giving players 10 marbles. Getting two into each of any four compartments would get a prize ticket. Getting a marble into the difficult fifth compartment would get another prize ticket, and more than one there would get two prize tickets. Among other things, these rules meant that there was the possibility of winning something right on up to the last marble, even if there was no hope of having two marbles in four of the compartments. The game was not only fun to play but also fun to watch, so we had a lot of observers as well as players throughout the day.

Our second gam e involved mounting some cones and rings on a tilted board, supplies that we had used for a previous fair. It went through similar testing and rule-creation. It wasn’t as successful, in part because it was very hard to win (despite our best efforts to make it more playable). Still, it was another activity that would be helpful for a day in which kids were not going to spend a lot of time running around outside.

e involved mounting some cones and rings on a tilted board, supplies that we had used for a previous fair. It went through similar testing and rule-creation. It wasn’t as successful, in part because it was very hard to win (despite our best efforts to make it more playable). Still, it was another activity that would be helpful for a day in which kids were not going to spend a lot of time running around outside.

This is a side note about the kind of community we are. Partway through the day, one of our students brought me a twenty-dollar bill that she had picked up off the floor. I asked the adults and children in the room at that time if anyone had dropped it, and — after a few adults checked their cash — all said it wasn’t theirs. A while later, a former student came up to ask if her father’s lost twenty had been found in our room, and I was happy to hand it to her. Trust and honesty are intrinsic to the way we engage with each other. I think we are exceptional in that regard.

We want to thank Deborah and the rest of the office staff for spending a lot of time figuring out how to best use our indoor spaces and motivate parents to come out on a dismal day. Their hard work before, during, and after the fair made it a success. Although we all hope for only sunny days for our fair in the future, they have created a plan that will stand up to any storm.

Week of May 1: Graduation is on the horizon . . . a bit of history

The month of May is the point at which we devote considerable time to preparing for graduation. For the fifth graders, it’s time to work on creating skits from funny anecdotes provided by the sixth graders’ parents. This is a tradition that has been part of graduation for more years than I have been at Miquon. My guess is that it was started to give the fifth graders some attention and importance that could balance with the amount of focus on their older classmates. Keeping the secrecy of the skits is incredibly important, and it is rare for our fifths to crumble under the endless questioning of the sixths. Silence is power.

We used to do the skits on graduation day, but that changed quite a few years ago when we had a graduating class of 25 students and were concerned about the length of the ceremony. The moving of the skits to the night before graduation and having an all-school family picnic has given it a more informal setting and truly puts the fifth graders into the spotlight. In music class, they start learning to play “Pomp and Circumstance” on kazoos — a touch of whimsy at the end of graduation itself. May is also the time that many of our fifth graders begin thinking seriously about the fact that they will be at Miquon for just one more year.

The sixth graders become involved with several graduation-related things. They make some decisions about the color and typeface of the “Class of 2017” t-shirts that they will wear to Skit Night. They run a couple of soft pretzel sales to raise money for their gift to the school, and they begin researching possible gifts by talking to staff and discussing their own ideas. As always, their own suggestions have ranged from the practical (more sports equipment) to the impossible (air-conditioning for the classrooms).

They start working on their music for the ceremony. In 1982, when the school was celebrating its 50th year, Tony Hughes wrote “Miquon in our Hearts,” which remains our much-loved official school song. Some years later, John Krumm was our music teacher. He wrote a beautiful second song for graduation — “Fields of Childhood” — that weaves its words and melody throughout the structure of Tony’s song and is performed by the graduates while the audience sings Tony’s composition. The graduates also choose one or two other pieces to do as well, usually ones that relate in some way to saying farewell to their school and community, and this occupies most of their time in music class during the month.

Most importantly, they begin creating their graduation speeches. Student speeches — where did they come from? I will confess to starting that tradition. Until we began it, our graduates were unheard throughout the ceremony until they sang at the end. But one year — too many years ago for me to recall just which one — I was on an accreditation committee for a neighboring independent elementary school. Part of their documentation mentioned that each of their 6th grade graduates stepped up to the microphone during their graduation ceremony to announce something about their experience that mattered to them — a word, a phrase, a sentence. Not much more. And I thought, we can do better than that. As it happened, our graduating class that year was quite small, so it looked like a good year to add something to what would otherwise be a very short ceremony. And we never looked back after that.

One year, something went wrong with the sound track on what was then a video-taped recording. There was a hum that disrupted the clarity of the students’ speeches. I took it to a local shop to see if it could be rescued. They put it on a player attached to a television in their showroom. Several adults who were not connected with the school stopped to watch and listen. One said with wonder, “All of those kids can speak!” Yes, they could. Although the hum could not be fixed, I’d like to hope that we got an enrollment or two out of that moment.

This speech-writing often seems to our sixth graders to be a daunting task at first, but it turns out to be a time of reflection, sharing of memories, laughter about funny experiences, and lots of thoughtful conversation as their texts evolve. Most students create three substantive paragraphs. We ask them to select a quotation that relates in some way to their message and write a few sentences that explain the connection. There’s a lot of conversation around those quotations. What do they mean, really? Who said those words, and what were the circumstances? The second paragraph is about their main idea. We ask them to write descriptively about something that they believe has been important in their Miquon experience. It may be about acquiring a new skill or interest, the value of friendship, learning to persevere in the face of difficulty, an exhilarating chase game or flying trip down the snow-covered tubing hill . . . the possibilities are enormous.

The most important thing, we tell them, is that it should be personal — a speech that only you could give. The third paragraph wraps it all up. And then they are ready to work on practicing their delivery. This all takes several weeks. The speeches go through many revisions in that time. Students often decide on a different quote as their ideas develop and change. Teachers focus on helping students express their ideas with clarity, and we do some coaching around grammar, but it’s important that the final text belongs entirely to the student and sounds like something created by an 11- or 12-year-old. We tell them that you may or may love public speaking, but it’s important to know that you can do it — because there are likely to be times in your life in which you will want or need to address an audience in support of something that matters to you.

Those gorgeous diplomas — they, too, were part of graduation before my time. But they were much less artistic and planned in my first years. Much less. They were done on big pieces of brown paper with markers, available in what was then the art room (now the after-school building) for anyone to stop in and write a celebratory description or memory on a child’s page. Now we devote several staff meetings to collect ideas from archived reports and recent memories, meetings that are filled with loving observations about each child’s growth, passions, and essential nature.

Before the building of the play barn, before the building of the graduation stage under a hired tent, before the invention of the wheel, we did the ceremony near the stream — close to where the monkey bars are now. Families brought blankets, graduates sat on folding chairs, and they were passed on to their middle schools with just as much love, optimism, and sense of loss as we do now. Later years saw a formal sit-down post-graduation luncheon evolve that became increasingly expensive for families. The graduates’ swim party was moved away from graduation day so the girls’ hair styling was not admired and lost in the same 24 hours. The diplomas became longer and more wordy, but not necessarily better or more personal.

We do seem to move in a world of continuing escalation, despite our best hopes for simplicity. Graduation is now more formal: parents work to create some lovely ambience on the stage, we hire a (nearly) storm-proof tent, and the diplomas are more artistic and thoughtfully-worded. We’ve tried to scale some things back a bit, nonetheless. The graduation luncheon is now a simpler reception with light snacks. Diplomas are a bit shorter. The graduates’ swim party happens in the week before the big event. Still, as we say every year to our students, you will have graduations that cost you more time, effort, and money, but you will never have another one that is truly all about you. Treasure it.

Before we know it, Graduation Day will be upon us. It’s just about a month away.

Week of April 24: Personal Projects begin . . .

Many years ago, when my husband, Tony, was the science teacher at Miquon, he did something that he called an Independent Science Project with the fifth and sixth graders. It was essentially self-selected and was meant to be done at home. His definition of “science” was very broad — I think rightly — so that the actual projects spanned an extremely wide range of activity. Students were expected to keep a journal that described what they were doing, what they were learning, and what kinds of problems they had to solve. For some students, this was a great success, and for others it was an endless opportunity for procrastination, last-minute hasty effort, and disappointment. Since specialists see students only twice a week (and sometimes just once if we are closed for a holiday or in-service), it was very hard for Tony to keep the procrastinators on track. At some point, after hearing him voice his frustration about collecting, reading, and responding to the student journals in a timely and helpful way, I suggested that it might get moved into the students’ home classroom. He agreed that daily oversight would be better for the students that needed it, so the Independent Science Project was reborn as the Personal Project.

Over the years, it’s gone through many evolutionary changes, but it’s essentially the same in its intent: we are giving students time to create or explore something new or to go deeper into an interest that they already have. We place tremendous value on supporting students’ interests, and this is one of the times in which they can be truly self-directed and fully in control of their work.

The first step, after they choose a topic and clear it with family and teachers, is to do a three-source inquiry that is meant to broaden their understanding of what they have chosen. It may lead them to change their topic completely, to narrow or enlarge it, or to affirm that they are going to like what they have selected. The sources might be websites, videos, books or magazines, and/or interviews. They write up a summary of the notes they have taken from the three sources and comment on how it has (or has not) affected their interest and their plans.

The next step is creating a written plan that lays out in some detail what they intend to do through the three weeks that the project runs. Mapping out the days, the times, and the specific goals will help them stay on track and, if necessary, make some adjustments to their working time or their anticipated outcome. We remind students that they will be doing some kind of presentation at the end of the three weeks. Keeping that in mind as they work will enable them to do such things as take photos of the doghouse they are building as it gradually comes together instead of just telling us about each stage.

This year, as always, we have a delightfully-varied collection of topics. Students’ choices include: composing music, cooking of several kinds, researching basketball and improving their own skills, dog training, photography, choreographing a trapeze routine, doing several kinds of art projects, learning to use a piece of software, and tracking imaginary investments in the stock market. We should have some very interesting presentations when all of this comes to an end later in May!

Week of April 17: Learning About Internment

- The Moved-Outers by Florence Crannell Means

- Japanese Roses by Theresa Lorella

- Desert Exile by Yoshiko Uchida

- Baseball Saved Us by Ken Mochizuki

- Farewell to Manzanar by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston

- Citizen 13660 by Mine Okubo and Christine Hong

- The No-No Boys by Theresa Funke

- I Am An American by Jerry Stanley

I also have a oersonal copy of Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp by Lily Yuriko Nakai Havey. Although some elements of the story seemed to me to be not quite appropriate for most of our students, the wealth of original paintings that illustrate the book are ones we will explore together in the coming week (using our document camera and projector).

Students have a document set up on their Google Drives to make brief notes about the books as they read them. We are asking everyone to read at least two books between now and the end of May — more, if their reading pace allows for it. Most students are now reading a second book and several are into a third.

We are discussing the stories on Wednesdays in a thematic way rather than gathering in separate groups for each title. This will allow everyone to get a broader understanding of the topic as they hear about other experiences. In those discussions, they’ll also be learning a bit about the history of Japanese-American relations from 1924 onward and, later, the Constitutional issues that were raised. the Supreme Court decision that upheld the action, and the financial compensation that was offered in 1948 and 1988.

In the first Wednesday meeting, we talked about how the students’ various books began — who is the central character, who else is in the family, where were they living before relocation, what did they do to support themselves, and how did they respond to the order to relocate? (One book takes place entirely after relocation, so students with that book needed to make some inferences.)

Last Monday, we asked students to choose a passage from their current book that they found especially meaningful and/or well-written. (A “passage” was anything from a paragraph to a full page.) We asked them to practice reading it aloud and to prepare to tell us why they chose it when we met on Wednesday. The selections were interesting and varied, and students gave clearly-explained reasons for their choice. In the discussion, they asked each other questions about the narratives and, in some cases, decided on what their next book choice would be, based on what they had heard in class.

Next week, we will ask students to focus on the adults, teenagers, and children in their books. How were the experiences and feelings of the people in those separate age groups similar and different? Among the adults, was it different for old people than for young or middle-aged adults? Were there any differences that depended on gender?

We’ll be making another title available to students next week: Bat 6 by Virginia Euwer Wolff. Bat 6 takes place after the internment camps are closed and families try to resume normal lives. It will have more meaning for our students after they have come to understand the impact of displacement and internment on the people in our other books. The author, Ginny Wolff, was a teacher at Miquon for a number of years in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and her children (Juliet and Anthony) are graduates. Ginny became a highly-respected author after leaving Miquon and moving back to her native Oregon. When she and I talked about the exploration of internment that I was doing with my class at that time, she shared her own childhood memories of seeing students from the camps return to her school and wondering how someone could be “away at camp” for years instead of just a summer.

We have made a number of connections to other topics. The forced migration of Irish Catholics to the west of Ireland in the 17th and 18th centuries, the uprooting of many of those people during the famine in the mid-19th century, and the heated rhetoric against Muslims and general immigration currently in the news have all come into our book conversations.

A side note about The Moved-Outers: This Newbery Honor book was published in 1945. I discovered it about ten years later while looking for something to read in my elementary school library and was astonished by the story. How could such a thing happen? I recall asking my parents about it and feeling dissatisfied with their explanation. It made enough of an impression on me that I have included it in my curriculum periodically so that those racist, unconstitutional, and unjust actions of our government will be remembered and, I hope, never repeated.

Week of April 10: Of food and holidays . . .

This past week, as you know, Passover and Easter converged on the calendar. We try to find time to talk about holidays of many kinds — their origin and meaning, the ways they are celebrated in our own community and in the wider world, and how they might connect to stories and ceremonies outside of the Jewish and Christian traditions. Our students have been exploring and discussing these two holidays and many others in their classrooms for quite a few years, so I’m always surprised when only a few students contribute what they know about them to our discussions. That was the case again this year. There was interest and there were questions, but the information itself was apparently sparse within the group.

We began talking about Christian period of fasting known as Lent several weeks ago, when Diane brought doughnuts for our building on the Tuesday before Lent began. We discussed fasting then — how and why it might be done, linked it to the daytime avoidance of food and water during Ramadan, talked about times in which Jews customarily fast, and what the Lenten connection was to Christianity as it led up to Easter. We talked about Mardi Gras (“Fat Tuesday”), Carnival, Pancake Day, Doughnut Day, and Fastnacht Day. As it was common in many places to avoid meat and all related products during Lent, the day before was often one of feasting and trying to use up all of the fat and meat in the house — hence, we have Carnival (carne = meat) and all those fried treats.

Several students shared information about Passover this week. We had talked about it before during our building sing, when we did some songs that had been created by enslaved black people before the Civil War. The songs linked the story of the captivity (and subsequent freedom) of the enslaved Jews in Egypt to the hopes that a similar emancipation would come to the slaves in the United States. We discussed the symbolic importance of food. What was on the Seder plate, and why? Interestingly, after one student discussed several of the usual items, another one said that there was always an orange on the plate at his house. An orange? Why? He told a story similar to this one that is shared by Anita Silvert at the website of the Jewish United Fund of Chicago:

It started with Dr. Susannah Heschel. The story you may have heard goes something like this: After a lecture given in Miami Beach, a man (usually Orthodox) stood up and angrily denounced feminism, saying that a woman belongs on a bima (pulpit) the way an orange belongs on a Seder plate. To support women’s rightful place in Jewish life, people put an orange on their Passover tables.

However, she goes on to say that the story is false and provides a different origin:

Heschel herself tells the story of the genesis of this new ritual in the 2003 book, The Women’s Passover Companion (JPL). It all started with a story from Oberlin College in the early 1980’s. Heschel was speaking at the Hillel, and while there, she came across a haggadah written by some Oberlin students to bring a feminist voice into the holiday. In it, a story is told about a young girl who asks a Rebbe what room there is in Judaism for a lesbian. The Rebbe rises in anger and shouts, “There’s as much room for a lesbian in Judaism as there is for a crust of bread on the seder plate.”

Though Heschel was inspired by the idea behind the story, she couldn’t follow it literally. Besides the fact that it would make everything — the dish, the table, the meal, the house — unkosher for Passover, it carried a message that lesbians were a violation of Judaism itself, that these women were infecting the community with something impure. So, the next year, Heschel put an orange on the family seder plate, “I chose an orange because it suggests the fruitfulness for all Jews when lesbians and gay men are contributing and active members of Jewish life.”

(You might enjoy reading more about this at the website linked above.)

We moved on to Easter. Like most Christian holidays, it carries with it many elements that are much older than and entirely unconnected to Christianity. After we talked about the execution and belief in the resurrection of Jesus, we talked a bit about foods commonly eaten on Easter Sunday and other times that there were traditional foods. One child asked about meat loaf. Meat loaf? He said yes, that he had heard that there was a holiday on which people were supposed to eat meat loaf. That left us all scratching our heads, but perhaps it’s true.

Finally, one child asked about all those eggs and the Easter Bunny. We explained that those were part of springtime celebrations and rituals that had their beginnings in Northern Europe long before anyone there had heard about Christianity. As often happened, Christians were able to connect local practices to their own teachings in order to support their efforts to convert people to a different world view. In this case, they linked their belief in the resurrection of Jesus to the resurrection of life in the earth after the bleakness of winter, so the traditions merged. There’s an interesting article about all that and more here.

Following tangents, as we often do, we compared notes about foods that most of our students find familiar but were perhaps not part of the diet of many of their parents or grandparents, depending on their own ethnicity and neighborhoods. Asian food, fresh produce that we can get out-of-season, food from Mexico and South America . . . pizza, sushi, fast food chains, tofu, quinoa, hummus . . . it goes on and on. When Mark and I said that those things were not part of our own childhoods, students were stunned. What did we eat?

We also discussed earlier influences on specific cuisines. Italians didn’t have tomatoes until they were brought back from the so-called New World and probably didn’t have pasta until travelers brought the idea of noodles back from Asia. It was Spanish conquistadores who found potatoes in Peru and started growing them back home, and it was the Elizabethan Sir Walter Raleigh who first planted them in Ireland. Diets change when we venture out of our own neighborhoods.

We encourage you to talk with your children about what you ate when you were growing up and what things were probably not part of your parents’ childhood food choices. It’s evidence that supports the many ways in which our students are growing up in a much more global community than previous generations did.

And one more thing about the Easter bunny —

In case you don’t recognize him, that’s Donald Trump’s press secretary, Sean Spicer, in the bunny suit at the White House Easter Egg Roll ten years ago . . .

Week of April 3: Irish history meets Irish tunes and songs

We’ve come a considerable distance in our study of Ireland. We started with geology — plate tectonics, the changing shapes and locations of lands and seas — and mythology, using a very brief version of The Book of Invasions where we learned about the giants, shape-shifters, and people of the goddess Dana who were believed in Medieval Europe to have been the first migrations to Ireland. After moving fairly quickly through the Celts and the arrival of Christianity, we then met the Vikings, who established the first towns as well as raiding the monasteries for their treasures. Invaders become settlers who are invaded by another group over and over — in Irish history and elsewhere. The Norsemen became the Normans in what is now France and invaded Ireland after they had gained control in England. As the Anglo-Normans became “more Irish than the Irish,” their assimilation became a concern to the English rulers, most notably Richard II and later, Henry VII. Rebellion and resistance, the shifting control of lands, and conflicts among the most powerful families as well as with England led to years of armed struggle.

Then came Henry VIII and his split with the Pope over his desire for a divorce from his first wife. At the same time, Martin Luther was raising questions (95 of them!) about the practices and integrity of the Roman Catholic church throughout Europe. What started out as a reform movement within the Catholic church became an increasingly-deep schism between the various groups of so-called Protestants and the traditional Catholics. We spent time on this on Tuesday, as much of this information was entirely new to the group and had them feeling a little confused about the difference between Martin Luther and Martin Luther King. We explained that one of the reasons that the founders of the United States wanted there to be a total separation between the national government and any specific religion was their knowledge of the turmoil that this linkage had caused in the past. Ultimately, what the Reformation meant to Ireland was that the secular conflict became entangled with religious differences. The legacy of that emotion-laden blend remains an issue in Ireland and Northern Ireland to the present day.

As the week ended, we had moved through the Tudors (including Elizabeth I and her meeting with the pirate queen known as Grace O’Malley), the reigns of James I and Charles I, the “Protectorate” era under Oliver Cromwell after Charles was executed, and the numerous waves of plantation settlers from England and Scotland who were under strict orders to avoid any kind of assimilation with the native population. As the plantations expanded, the Catholic Irish were moved off their lands and pushed into the less-fertile western province of Connacht. We’ve had some interesting tangential conversations. Cromwell’s name is hated in Catholic Ireland to this day — but the worst actions were done by his successors. Isn’t this a bit like naming Columbus as the singular villain of New World colonization and atrocities? How is some of what we are learning about the plantation of settlers in Ireland similar to what went on in the United States as our wagon trains full of settlers went west? Why were they encouraged (through the promise of free or cheap land as well as an appeal to their patriotism) by the government to take such a risky journey? How did the split within Christianity affect the alliances and clashes among Catholic France and Spain and Protestant regions such as the Dutch Republic in the Netherlands as well as Great Britain? All of this is very new material for most of out students, and we aren’t expecting them to remember all of it or understand the full complexity. At the same time, we’ve heard some excellent insights and questions as we’ve read, watched videos, and talked.

As I keep reminding our students, any fragment of these times and places could form a topic of study for a full year (or more). But our goal is to give them a learning experience that is different from what they have done before — not a deep look at a short time period, place, and/or event (such as ancient Egypt or the Civil Rights movement) but a longitudinal sweep across a single place from its geological beginnings to the current day. Those boundaried studies of specific events don’t occupy an isolated place — they are part of a whole mainland of history rather than being detached islands, and the causes and effects go on and on in both directions..

Our students are starting to make some wonderful connections. One child commented this week on the fact that we are getting close to the time of the American Revolution, and that he could now see the problems facing Britain in their efforts to control the distant 13 colonies because they were also engaged in conflicts in Ireland and in the rest of Europe that consumed money, troops, and political attention. Some of the tunes and songs that we have been doing on our pennywhistles and in our Wednesday sing have taken on new meaning. As we watched a video documentary about Irish history, they were interested to see a statue of Thomas Moore, who wrote the words to “The Minstrel Boy.” They also saw and responded to a painting of Turlough O’Carolan, who composed (among many other tunes) “Planxty Fanny Power.” We’ve been playing that on pennywhistle for a while, always taking a moment to giggle over how the title name sounds to our modern ears. In the video, they heard O’Carolan described as a musician who “straddled both worlds” in Ireland — composing tunes in the classical style for the Protestant Ascendancy but still being an itinerant harper in the ancient tradition. When students saw that the first performance of Handel’s Messiah took place in Dublin in 1742 and heard some of the music played, most recognized it and, again, felt that something had acquired a new context.

We have a lot of enthusiastic pennywhistle players in our group at this point. Without being asked, some have brought their whistles to our Wednesday sing to accompany The Minstrel Boy. We are finding a place of convergence with Diane and Jeri’s study of the American Civil War as that song had 2 more verses added at that time, almost certainly by an Irish immigrant soldier in the Union army, probably serving in what became known as the Irish Brigade. We’ll be adding to those opportunities to find common ground among our two social studies topics, our sing, and our pennywhistle playing.

Finally, a bit of a personal and tangential information. I got an email this weekend from Sam Agre, a Miquon student who is now about to graduate from American University. He said that he was cleaning out his “old room” (which I took to be at his family home) and discovered his pennywhistle. He was wondering if I could send him some of the tunes we had done when he had been in our class, as he would like to start playing again. And, of course, I will. You never know, do you? It really made me smile.

Week of March 13: no time to blog substantively this week — sorry!

This was another full but fragmented week. Tuesday was a snow day, Wednesday was a personal snow day for me (and, if you’ve seen the road to my house, you’ll understand why), we had a guest speaker on Thursday (Russell Janzen, a Miquon graduate and now a principal dancer in the NYC Ballet) , and had a teacher candidate doing demonstration teaching for most of the day on Friday. Look for descriptions of our guest in news coming from the Miquon office. At this point, all of my time is going into preparation for our Conference Week, and the next informative blog post will have to wait until we get back from spring break. I hope everyone enjoys some family time while their kids are not in school.

Week of March 6: Stories and Buddies

This week, we began working on a play that we hope to have ready to perform by the end of April. The story is called The Táin, or The Cattle Raid of Cooley. (Irish has some very different phonics rules — the title is pronounced TAWN.) It’s one of the most well-known parts of a lengthy group of tales known as the Ulster Cycle. Our version of the play is considerably simpler than the full story and is based on a little book of the same name by Liam Mac Uistin. (You can learn more about the story here and also here, among other sites.) The tale centers around the foolish actions of Queen Maeve of Connaught. In an effort to ensure that her wealth is greater than her husband’s, she starts a war to gain possession of a famous bull. Opposing her is the young Ulster hero, Cuchullainn. As she and her allies suffer increasing losses, she becomes more and more intent on victory at any cost. It’s a story of love, jealousy, greed, and courage. It shows the position of cattle as wealth in ancient Ireland, the independence and high status of women, the political aspects of the child-raising practice known as fostering, and the belief in the intervention of deities in the lives of ordinary mortals.

Before embarking on this play, students read many different stories that come from Irish tradition. We decided to choose a few to work up as short skits, with the intention of performing them for our buddies in Bree and Rich’s first/second grade group. Although we spent minimal time creating costumes and props, there were some very imaginative solutions. Blue paper on the floor was a river, folded newspaper built the Giant’s Causeway, and a bit of cleverly-placed Scotch tape enabled a druid to spear a fish. After one group realized that two sticks taped together didn’t make a very satisfying slingshot, they took to the woods with saws in search of a forked branch.

After several delays for other projects, we got that all together this week and invited our buddies to our classroom on Wednesday afternoon.

When the four skits were finished, our students had time to read more Irish folktales with their young friends.