Fair weather, fair hair, the Miquon fair, a fair share, fair game, fair and square, no fair . . .

What a word! Our students often question fairness when they talk about a game or when treats are being distributed. It frequently means that they were disappointed in some way and wished for a different outcome. But what do we really mean by fair?

It comes into our classroom in many ways. Students sometimes “shoot for it” when there is something to be won — the first turn, a contested seat at a table, or deciding who gets a certain part in a play, for example. Rock-paper-scissors is one procedure that they choose, a ritualized process that is known in some form all over the world. Its origins seem to go all the way back to ancient China, somewhere around the third century BCE. Japan, however, is apparently the place from which the worldwide spread began. If you want to know a lot more about it, including how it applies to bacteria and to the mating strategy of a particular lizard, go here.

The “weapons” vary greatly worldwide. Recently, some players have added “lizard” and “Spock” to their arsenal. Whatever is used, it is essentially a zero-sum games, although skill comes into it when you get to know your opponent’s typical behaviors. Is it a fair way to settle something or just enjoy it as a fair game? Essentially, yes, but it works as a decision-maker only for pairs of players.

So what can our students do when three people want to be the Main Bunny in the play? We teach students to use a one-or-two finger process. Three people put their hands behind their backs and, on the count, bring their hands forward and put out one or two fingers. As soon as someone doesn’t match the other two, the winner (or loser) is that person. Why is this better than just doing RPS twice? It’s more fair because all three players are involved in the same number of games. With something like a coin toss to find a winner among three players, one person has to play twice, but the winner could be the person who played only once, beating the winner of the first paired contest.

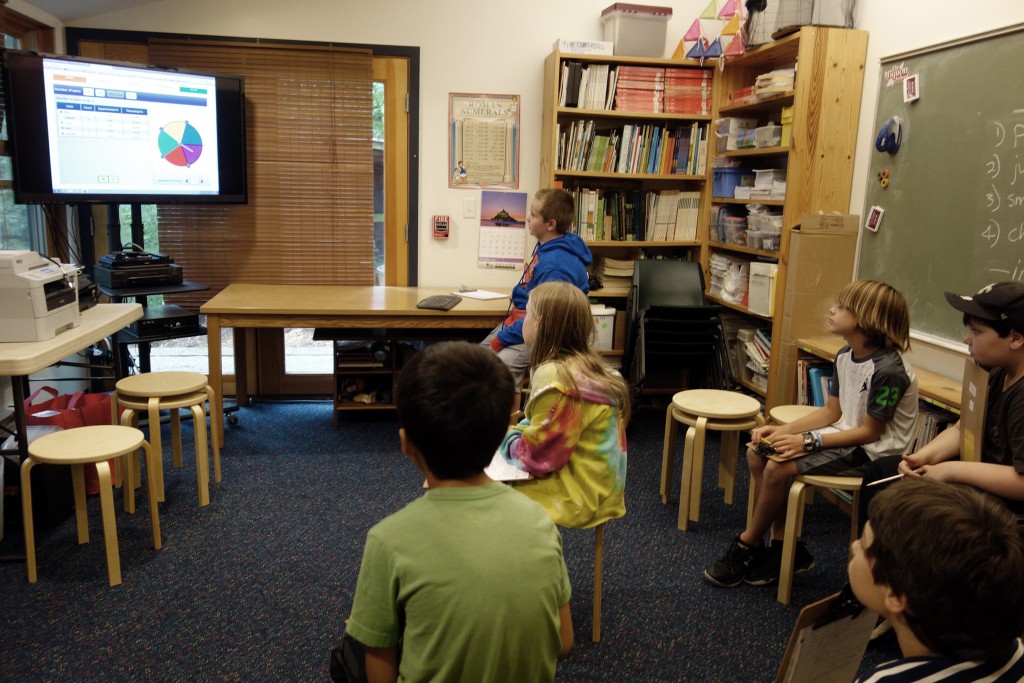

We brought fairness into mathematics last week when we asked students to design a spinner game. We talked about what fair means in a mathematical sense. Students quickly suggested that it meant equal odds or equal chances for all of the players. We discussed a worksheet on which a spinner was displayed and analyzed the rules for the game that went with it. The 8 regions in the spinner were worth a different number of points (from 1 to 8). Each player’s scoring system was unique: one always multiplied the region’s points by 2 while the other added 4. Whoever got the most points on a given spin would be the winner of that round. We asked students to prove that the game was or was not fair. They struggled for a while but gradually realized that creating a chart with all of the outcomes and the separate scoring methods would be a good strategy. It turned out that the game favored the player who doubled the number on the spinner region. Students came up with several different changes to the game to make it fair.

Then we went to NCTM’s Illuminations website, where one of the tools available was a spinner that could be modified. The assignment was this:

1. Create a FAIR game for 3 people that uses at least 5 sectors on the spinner.

a. Write out the rules for the game.

b. Make sure you explain the scoring.

c. Create a chart which shows that it is fair (like the one you made to test the fairness of the game on today’s work sheet).

We got some clever, simple, complicated, and (mostly) fair results. Students explained their games during several math classes. Although most designed a point-winning game, one student’s game required being the first to land on all of the regions at least once. We had a lot of fun testing and playing each other’s creations.

One more application of fairness is embodied in the way we do social problem-solving. With very few exceptions, our approach is to get all of the involved students together so they can all hear other people’s perspectives on the issue as well as have a chance to voice their own views. Sometimes just hearing from others leads everyone to arrive at a peaceful resolution. Sometimes it takes longer and could require more than one meeting or a different format for the discussions. But the process is meant to be as transparent as possible, so that — whatever the outcome — most or all of the students will judge it to be fair.